This is the ninth in the Whoa!Canada: Proportional Representation Series

This is the ninth in the Whoa!Canada: Proportional Representation Series

Rep By Pop

Canadians have been arguing about how we should vote since before Confederation.

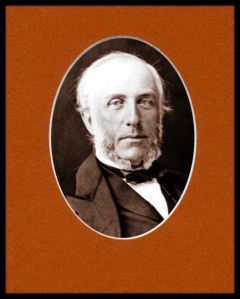

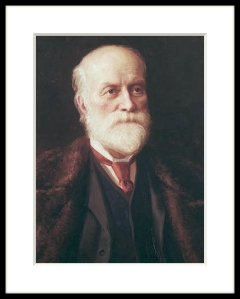

At that time, Upper Canada (what would become Ontario) and Lower Canada (what would become Quebec) had equal representation in government. When the system was initially put in place, the French population outnumbered the English, but by the time of Confederation, only about 40% were French. If Upper Canada’s George Brown had his way, the government of the new Dominion of Canada would be elected with Rep by Pop (Representation by Population) in which every vote cast across the Canada would be equal.

Since the regions that were contemplating federation were unequally endowed in population, compromise was needed, so the decision was made to establish proportionate representation among the provinces.

Every province and territory is allocated a certain number of seats in the House of Commons according to a formula set out in section 51 of the Constitution Act, 1867, along with other historical seat guarantees found in the constitution.”

— Electoral Systems and Electoral Reform in Canada and Elsewhere: An Overview: 2.1 Canada’s “First-Past-the-Post” Electoral System

In 1892 the renowned Canadian engineer and inventor Sir Sandford Flemming lobbied for the implementation of Proportional Representation with “An appeal to the Canadian institute on the rectification of Parliament.” Unfortunately, then, as now, powerful forces were employed to preserve the unfair status quo.

Still, the idea of embracing Proportional Representation in order to attain electoral fairness didn’t die out. Voting reform has moved to the forefront as Canadians have become increasingly aware that our votes don’t count.

Recommended for Canada

Over the years the inadequacies in Canada’s Voting system has resulted in much study.

- 1977: Manitoba Law Reform Commission Working Paper on Electoral Reform recommended Single Transferable Vote (STV) in urban areas.

- 1979: Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s Pepin-Robarts Commission recommended Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) for Canada

- 1984: Quebec Electoral Representation Commission tabled a report recommending Proportional Representation

- 2003: Quebec’s Estates General on the Reform of Democratic Institutions recommended Mixed Member Proportional (MMP)

- 2003: Prince Edward Island’s Hon. Norman Carruthers Report recommended Mixed Member Proportional (MMP)

- 2003: Quebec government study led to a Quebec government recommendation of MMP

- 2004: The Law Commission of Canada 3 three-year study/Consultation recommended Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) for Canada

- 2004: British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform recommended Single Transferable Vote (STV)

- 2005: New Brunswick’s Commission on Legislative Democracy recommended Mixed Member Proportional (MMP)

- 2006: Quebec Citizens’ Committee Report recommended Mixed Member Proportional (MMP)

- 2006: Quebec Select Committee Report recommended Mixed Member Proportional (MMP)

- 2007: Ontario Citizens’ Assembly recommended Mixed Member Proportional (MMP)

- 2007: Quebec Chief Electoral Officer’s Report recommended Mixed Member Proportional (MMP)

[Note: For more detail on the list of 13 recommendations please visit Fair Vote Canada’s Thirteen Canadian Commissions, Assemblies and Reports that have recommended proportional representation Page (archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20160424083901/http://www.fairvote.ca/reports/)

Electoral Systems

We tend to think the ballot has more power than it actually has because it is the public face of the election contest. It’s our user interface. Which is why it is important for the ballot to be easy for voters to understand— voters shouldn’t have to come out from behind the privacy screen in the voting station to ask the poll clerk how their ballot should be marked. Voters need to be able to indicate their preference if they are to have any hope of electing the Member of Parliament that will best represent them. But the ballot is still just one of the elements of electoral system design.

The procedure by which qualified voters determine who our representative will be is called an electoral system. The different elements that go together to make up an electoral system determine:

- the structure of the ballot

- how votes are cast

- the way votes are counted, and

- the criteria needed to win

At this point most Canadian electoral reformers have a very good idea which voting systems are more likely to go over well with Canadians. Because this is such a confusing topic, I have chosen to limit this article to the electoral systems that might actually6 be used in Canada.

Plurality or Majority

Only one winner is possible in a winner-take-all voting system. Just as it sounds, at the end of the election contest, one winner gets it all, the candidates who against them are losers, the citizens who voted for them are left without effective representation in Parliament.

FPTP

FPTP

First Past The Post • Single Member Plurality

The voting system we have been using federally in Canada since Confederation. It may appear as if we have one Canada wide election, but in reality we actually elect Members of Parliament in 338 individual winner-take-all elections.

The area within each province is divided into separate electoral districts, or ridings, each represented by a single member of Parliament. During an election, the successful candidate is the individual who garners the highest number of votes (or a plurality) in the riding, regardless of whether that represents a majority of the votes cast or not. The leader of the party that secures the largest number of seats in the House, and can therefore hold its confidence, is generally invited by the Governor General to be the prime minister and form government.”

And, of course, this is the voting system Mr. Trudeau vowed to replace.

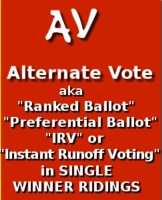

AV

AV

Alternative Vote

majority-preferential

Preferential Voting

PV

Preferential Ballot

PB

Instant Runoff Voting

IRV

Ranked Ballot

The system is most accepted in single winner elections (as for Mayor or President,) but tends to be found wanting when electing legislative bodies because doesn’t produce outcomes very different than our current winner-take-all First Past The Post system.

Alternative Vote (AV):

This system is also known as preferential voting.

On the ballot, voters rank the candidates running in their riding in order of their preference.

To be elected, a candidate must receive a majority of the eligible votes cast.

Should no candidate garner a majority on the first count, the candidate with the fewest votes is dropped, and the second preferences on those ballots are redistributed to the remaining candidates.

This process continues until one candidate receives the necessary majority.— Electoral Systems and Electoral Reform in Canada and Elsewhere: 3.1 Plurality or Majority Systems

Over the years Alternative Vote has been adopted here and there through out the world for varying periods of time. Here in Canada the province of British Columbia used AV in its 1951 and 1952 elections, Alberta and Manitoba used AV in rural ridings for about three decades ending in the 1950s.

The only country that has used the Alternative Vote system at the federal level of government for any length of time is Australia, where this winner-take-all system was adopted in 1918. But the 1948 majority government decided to implement the Single Transferable Vote Proportional Representation to its Senate elections.

But a fresh review of the historical record shows that the 1948 decision was really the final stage in a frequently-deferred plan of parliamentary reform that goes back to Federation. Even before Federation, many prominent constitutional framers had expected the first Parliament to legislate for proportional representation for the Senate. Sure enough, the Barton government included Senate proportional representation in the original Electoral Act, but this was rejected in the Senate on the plausible ground that it would undermine the established conventions of strong party government.”

— Parliament of Australia: Why We Chose Proportional Representation

A mix of Alternative Vote (majority-preferential) and Proportional Representation (quota-preferential) can also be found in Australia’s provincial Upper and Lower Houses.

Although this system is so little used, the data is fairly consistent. New and small parties are allowed to participate, but the system is designed to funnel their votes back to the major parties, so although voters may be freer to actually vote for the candidate that would best represent their interests in Parliament, they are unlikely to ever elect them.

Because Alternative Vote raises the bar to 50%+1, Alternative Vote makes it even more difficult to elect women and minorities than under First Past the Post.

Alternative Vote is thought to provide an edge to centrist parties because centrist parties are likely to be the second choice of voters on both left and right. But this is still a winner-take-all system that leaves too large a proportion of Canadians without representation in Parliament.

Adopting Alternative Vote would give the appearance of change while effectively retaining the status quo.

Does any electoral system have more aliases than Alternative Vote? Proponents of this system seem to be continually rebranding their favored winner-take-all electoral system, presumably to better market it to voters. This proliferation of names for the same system adds a great deal to the confusion around voting reform.

You might have noticed that Fair Vote Canada’s Thirteen Canadian Commissions, Assemblies and Reports that have recommended proportional representation Page doesn’t include a single recommendation for Alternative Vote.

Proportional Representation

While Alternative Vote is a single system with many different names, the defenders of the status quo very often give the impression that Proportional Representation is a single electoral system. This tactic frees them to cherry pick the worst examples of problems found among the 90+ countries that have adopted Proportional systems over the last century or so to “prove” this will happen if we adopt Proportional Representation.

Proportional Representation is not a single electoral system, it is the name given to the family of electoral systems that share the principle of proportionality. The one good thing about Canada’s tardiness in attending the Proportional Representation party is the wealth of data from which we can learn about successes and failures experienced by other countries. This way we can avoid the pitfalls while cherry picking the features we need to get the benefits we want from electoral reform.

The phrase “Proportional Representation” describes the outcome of elections in which the voting system ensures seats in Parliament are won in the proportion in which votes are cast. Which is to say 39% of the votes would equal 39% of the power in the legislature.

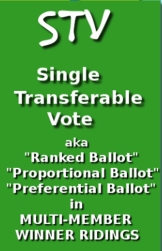

STV

STV

Single Transferable Vote

quota-preferential

ranked ballot

Proportional Ballot

Preferential Ballot

At a glance, the Single Transferable Vote looks very much like Alternative Vote. After all, both systems make use of the ranked ballot.

Very often the proven benefits of STV (the Single Transferable Vote) are mistakenly cited as benefits that would be achieved with Alternative Vote.

Single Transferable Vote (STV):

Citizens in multi-member ridings rank candidates on the ballot.

They may rank as few or as many candidates as they wish.

Winners are declared by first determining the total number of valid votes cast, and establishing a vote quota (or a minimum number of votes garnered); candidates must meet or exceed the quota in order to be elected.

Candidates who receive the number of first-preference votes needed to satisfy the quota are elected. Any remaining votes for these candidates (that is, first-preference votes in excess of the quota) are redistributed to the second choices on those ballots.

Once these votes are redistributed, if there are still seats available after the second count, the candidate with the fewest first-preference votes is dropped and the second-preference votes for that candidate are redistributed.

This process continues until enough candidates achieve the quota to fill all available seats.

In order to retain the size of the legislature, riding boundaries would need to be redrawn, so existing electoral districts would be amalgamated into larger districts. Voters can vote exclusively for the candidates they feel would represent them best, and partisan voters would have the opportunity to rank the candidates in their favoured party. Single Transferable Vote achieves proportionality naturally, without giving political parties any extra advantage.

Single Transferable Vote achieves proportionality simply by increasing the number of MPs that would represent each district. When only a single winner is possible, every party scrambles to run the candidate most likely to win most of the votes. This generally results in a pretty homogeneous bunch of candidates; in Canada it almost always means a white male. This is why Canada has such an abysmal record of electing women and minorities to our legislatures, in spite of our vaunted multicultural diversity. Around the world Proportional Representation has a track record of electing governments that better represent the diversity of the electorate. STV seems to do this best.

As I understand it, the difficulty in applying STV to a geographically enormous country like Canada can be quite a challenge. In order to achieve a reasonable level of proportionality, there must be a large enough number of enough MPs. Nine to Twelve member districts would be ideal, but would prove impractical. Such a system would require a fair bit of made-in-Canada tweaking for STV to be made to work effectively across this great nation.

Still, this is the 21st Century. We live in a time when digital technology has made two way communication with far away people not only possible, but easy. The Internet helps shrink enormous geographic distances into workable communities.

MMP

MMP

Mixed-Member Proportional

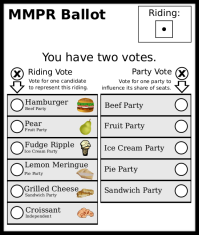

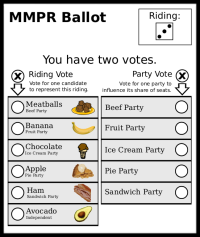

MMPR

MMPRS

Additional Member System

AMS

You may have noticed this is the electoral system that has been most often recommended for Canada in the Recommended for Canada section near the top of this article. What you won’t see from my list is the many different ways of implementing a made-in-Canada version of MMP detailed on Fair Vote Canada’s Thirteen Canadian Commissions, Assemblies and Reports that have recommended proportional representation Page.

That’s the thing about MMP, it is an extraordinarily customizable system. Whenever anyone says, “this is MMP” and begins to explain it to you, chances are they are explaining their favoured rendition of it. The Canadian Government website’s description isn’t quite right, nor do I much like the UK Electoral Reform Society’s explanation of their version of MMP called Additional Member System as used in the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Assembly, and the Greater London Assembly.

That’s the thing about MMP, it is an extraordinarily customizable system. Whenever anyone says, “this is MMP” and begins to explain it to you, chances are they are explaining their favoured rendition of it. The Canadian Government website’s description isn’t quite right, nor do I much like the UK Electoral Reform Society’s explanation of their version of MMP called Additional Member System as used in the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Assembly, and the Greater London Assembly.

What we all agree on is MMP is a hybrid system combining a Plurality and List PR systems, imposed on post WWII West Germany by the Allies.

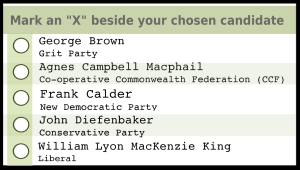

The ballot comes in two parts, one side contains a list of candidates, and the voter marks an “X” beside the name of the chosen candidate.

The voter is expected to mark an “X” to indicate their favoured party on the other side of the ballot.

Everything is changeable.

Although the Candidate/Constituency side of the ballot is generally a First Past The Post ballot, it could just as easy be a ranked AV or STV style ballot. The Party side of the ballot also results in MPs, so the proportion of MPs on both sides is variable too. There might be more party MPs or less, or they could just as easily be the same.

But the most changable portion of the MMP vallot is the Party side. This is where we get into lists. There are three kinds of lists:

Closed List MMP

The list of candidates is decided by the party. The party ranks its candidates in the order in which it wants them.

Open List MMP

The list of candidates is included on the ballot, and the elector can vote for specific party candidate they like. This side of the ballot might be done with an “x” or it might be ranked.

The list of candidates is included on the ballot, and the elector can vote for specific party candidate they like. This side of the ballot might be done with an “x” or it might be ranked.

Listless MMP

As the name suggests, this system includes no list, like the Fair Vote mock Election MMPR ballots pictured here. In this type of system, the candidates on the first side are elected in the usual way, and the list side candidates are determined from among the candidates who were not elected. The party that needs 2 top-up candidates would get seats for their two unelected candidates who received the most votes.

Former Liberal Party Leader (and current cabinet minister) Stéphane Dion developed his own version of MMP he calls P3

DMP

Dual Member Proportional Representation

Dual-member Mixed Proportional

Dual Member Proportional (more formally known as Dual-member Mixed Proportional) is a proportional electoral system that was created by Sean Graham in 2013 with funding from the University of Alberta’s Undergraduate Research Initiative. It was designed to meet Canada’s unique needs and to bridge the gap between Single Transferable Vote and Mixed Member Proportional advocates.

— About DMP

Existing single member electoral districts would be amalgamated into 2 member ridings, so no new seats would need to be added to the Assembly. Each Party can field up to two candidates in each riding, but voters each cast only a single vote, either for an Independent candidate, or one of two ranked candidates running for a party (or only one party candidate if only one is nominated).

Each district would elect two MPs, the 1st candidate in the party with the most votes would win the first seat, and the second seat would be used to ensure overall proportionality.

A nice twist is that Independent candidates get a little edge; if an Independent candidate comes first or second, s/he will be guaranteed a seat.

This made-in-Canada Proportional system was been chosen to be one of the electoral systems included in the upcoming referendum scheduled to take place in November 2016 in Prince Edward Island.

So there you have it. If you are interested in more detailed information, both Fair Vote Canada and Wikipedia are good sources. Also, check out my PR4Canada resources page (which has a link in the sidebar).

Next up will be my Voting Glossary.

Erratum

Although I will correct a typo, rearrange text for clarification or clean up other formatting errors without comment, when I make a substantive change to the content of an article published online, I always make note of it, as I am doing here: I’ve removed the following error of fact from the section about AV (Alternative Vote) above: “Since adopting AV, Australians have only ever managed to elect candidates from the three main parties to their House of Representatives.”

Thanks to Geoff Powell of PRSA (Proportional Representation Society of Australia) for pointing out my error:

“Adam Bandt (Greens) is the member for Melbourne in the House of Representatives. Independents have been elected to the House, but usually after falling out with the party under whose banner they were originally elected. Greens are making inroads in inner Melbourne and Sydney as these areas become gentrified. Of course Greens get close to their fair share in the [Proportional] Senate despite its malapportionment.”

Thanks, Geoff!

• Proportional Representation for Canada

• What’s so bad about First Past The Post

• Democracy Primer

• Working for Democracy

• The Popular Vote

• Why Don’t We Have PR Already?

• Stability

• Why No Referendum?

• Electoral System Roundup

• When Canadians Learn about PR with CGP Grey

• Entitlement

• Proportional Representation vs. Alternative Vote

• #ERRÉ #Q Committee

• #ERRÉ #Q Meetings & Transcripts

• Take The Poll ~ #ERRÉ #Q

• Proportionality #ERRÉ #Q

• The Poll’s The Thing

• DIY Electoral Reform Info Sessions

• What WE Can Do for ERRÉ

• #ERRÉ today and Gone Tomorrow (…er, Friday)

• Redistricting Roulette

• #ERRÉ submission Deadline TONIGHT!

• #ERRÉ Submission by Laurel L. Russwurm

• The Promise: “We will make every vote count” #ERRÉ

• FVC: Consultations Provide Strong Mandate for Proportional Representation #ERRÉ

• PEI picks Proportional Representation

• There is only one way to make every vote count #ERRÉ

• Canada is Ready 4 Proportional Representation

• Sign the Petition e-616

• #ProportionalRepresentation Spin Cycle ~ #ERRÉ

• International Women’s Day 2017 ~ #IWD

• An Open Letter to ERRÉ Committee Liberals

and don’t forget to check out the PR4Canada Resources page!

” This is why Canada has such an abysmal record of electing women and minorities to our legislature, in spite of our vaunted multicultural diversity. Around the world Proportional Representation has track record of electing more diverse governments that better represent the diversity of the electorate. STV seems to do this best.”

The two main countries that use STV, in its pure form, are Malta and Ireland. Both have had abysmally low levels of female representation: Ireland’s national legislature has 22% female members, and Malta only 13%. I see little evidence that STV is especially good for female representation.

I also see a substantial problem with ‘dual member proportional representation’. It seems fairly easy to strategically manipulate. Were I a party organiser in a district where my party was dominant, I might run an ‘independent’ candidate, and then divide the votes in the district between the ‘independent’ and my party’s official list.

Also, would be good to see some mention of pure open list PR. This often acts the same as MMP, in terms of seat distribution. However, it allows intraparty competition, which is often not allowed under (normally closed-list, to ensure ballot simplicity) MMP. It is also used more commonly around the world than many of the other mentioned syste,s

I don’t know enough about the culture of either country; but I do know that voting system is not the only factor. In Canada our determinedly feminist Liberal Party with a FPTP majority did an abysmal job of electing women. Mr. Trudeau’s gender balanced cabinet created an incredible imbalance in the LPC backbenches. The only reason Canada has as many women in Parliament as we do is because the NDP has been giving female candidates preference.

STV does put voters in the driver’s seat, but they need to have choices. If they do, and voters want to elect more women, they will. If there aren’t good female candidates, or enough, then the record won’t be good. But gender is not the whole story. In the American Democratic Party primary there is an excellent chance the female contender will get passed over in favour of a male contender with a better record on women’s issues. Of course, if our American friends are really clever, they will elect Jill Stein their first female President.

List PR is not on the menu in Canada. In spite of the fact most Canadians vote for parties and leaders, local representation is one of our major criteria.

Of course gender isn’t the whole story, although I doubt at this point there’s an excellent chance the female candidate will be passed over. However, I was saying that I haven’t seen much evidence that STV does much for female representation (compared to on its own. I agree with you that, if that is important, parties need to act.

I can’t see why List PR would destroy local representation. Sure, national closed list would do so. But you can mix local open lists with a national compensatory list, as is done in Greece and Denmark.

The ideas around what Canadian voters might or might not want have been worked out by Canadian electoral reformers over years, if not decades. I’m just sharing what I’ve learned/am learning.

Sean Graham’s dual candidacy proportional system is extremely similar to what I had come up with recently, or I should say mine looks like his.

I dubbed it “tandem district mixed proportional”. The main difference being that individual candidates are voted for, and in the district (or first) votes the tallies are combined for the two of the party’s candidates, with the leader among them being elected to the seat, and the loser being returned to the party list with their individual votes only. This allows voters to hold members accountable without fear of the party losing favouribility within the district.

Furthermore, I considered enforcing mixed genders in the tandem, as well as term limits for members who consistently fail to achieve a threshold.